Part I of V in the series: “Under the Lash and the Lie”

I write this not as a detached historian, but as a Black person whose blood carries the memory of screams that echoed through the cane fields of Jamaica and the cotton fields of the American South. My ancestors were enslaved. Their bodies were currency, their wombs weaponised and their pain deliberately buried under centuries of silence. But silence is a kind of death and I refuse to let their stories die. This series is an act of reckoning and I begin where the violence was most intimate: the sexual terror inflicted on Black women and girls.

“There is no shadow of law to protect her…”

Harriet Jacobs, an enslaved woman in North Carolina who escaped and later wrote her memoir Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, laid it bare:

“No matter whether the slave girl be as black as ebony or as fair as her mistress, in either case there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence, or even from death; all these are inflicted by fiends who bear the shape of men.”

What Jacobs described was not the exception, but the rule. On both Jamaican sugar estates and Southern U.S. plantations, the sexual violation of Black women and girls was not only common it was a foundational feature of slavery. Rape wasn’t just a tool of domination; it was an economic strategy.

Slavery’s Logic: Wombs as Capital

After Britain ended the trade in slave in 1807, (the practice of slavery continued until it was eventually officially outlawed in 1833) enslaved women in Jamaica became even more valuable not just for their labour, but for their ability to reproduce future labourers. In the United States, this was already the case. Virginian slaveowners like Thomas Jefferson who himself fathered children with the enslaved Sally Hemings openly calculated the increase in the enslaved population as an asset on their balance sheets.

To them, Black women’s bodies were not human but productive property. As scholar Jennifer L. Morgan puts it in Labouring Women, “African women’s reproductive labour was imagined not in terms of family or community, but in terms of the reproduction of property.”

It is no accident that the law of partus sequitur ventrem that a child follows the status of the mother, meant the children born of rape were automatically enslaved. There was no legal consequence for rape. There was instead, reward.

The Scale of the Violence

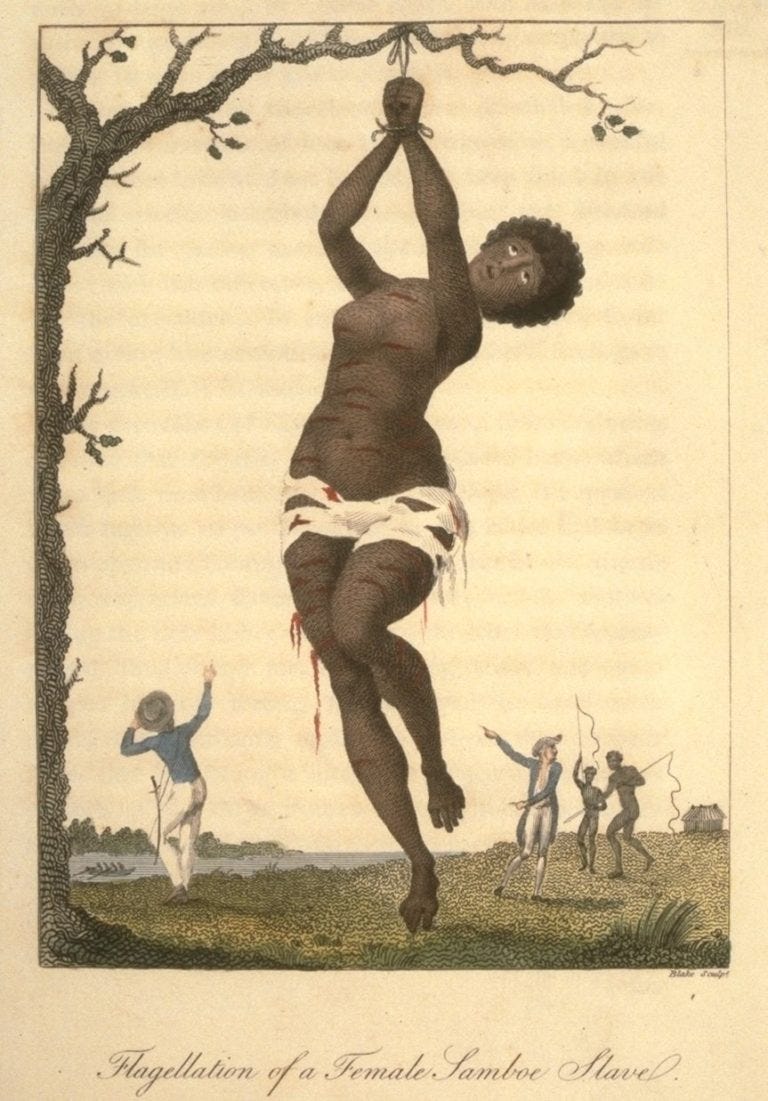

In Jamaica, the sheer brutality of slavery, driven by sugar’s deadly profits, meant many enslaved women were sexually assaulted by white planters, overseers and militia men. British absentee landlords rarely visited the estates, leaving power in the hands of men with no checks on their behaviour. Contemporary travel writer Edward Long casually described enslaved women in hypersexual, animalistic terms, helping to create a justification for their abuse.

In the U.S., the violence was no less horrifying. On plantations in Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina, enslaved girls as young as 10 were forced to bear children. They had no choice over their partners. Sometimes enslaved men were bred with them like cattle. Sometimes it was the master, or his sons, or a neighbour. The resulting children were often sold away from their mothers, compounding the trauma.

Even abolitionist narratives, such as those of Frederick Douglass, hint at these horrors. He never knew his father but understood he was white. “The means for knowing was withheld from me,” he wrote, “and the master’s guilt was shielded by the silence of the law.”

Names We Do Not Know

There are countless women whose stories were never written, never recorded whose names were erased by time and white indifference. But we can hear them if we listen.

We can hear them in the creole lullabies passed down through Jamaican grandmothers. We can hear them in the broken lineages, the family trees that stop mid-branch. We can feel them in the aching silence when someone asks, “Where did your people come from?” And we answer only with pain.

Survival, Resistance, and the Sacred Act of Telling

Despite it all, Black women resisted. Some ran away. Some practiced abortions using traditional herbs. Some killed their abusers. Others told their stories to the rare few who would listen historians, missionaries, writers. They passed on truth the only way they could: through whisper, prayer, song.

To tell these stories now is not just an academic act. It is a spiritual one. It is to recover a humanity that was deliberately stripped. It is to stare back at the past without blinking.

Why This Series, Why Now

I am writing this series not simply to document brutality, but to confront its legacy. The rape of enslaved Black women helped birth the myth of Black hypersexuality, the Jezebel stereotype that still haunts how society treats Black women today from media portrayals to legal systems that often fail to believe them.

This history explains the silence. It explains the shame that isn’t ours but has been passed down to us like an unwanted inheritance. But we do not have to keep it.

We can name it.

We can write it.

We can refuse to be ashamed of surviving.

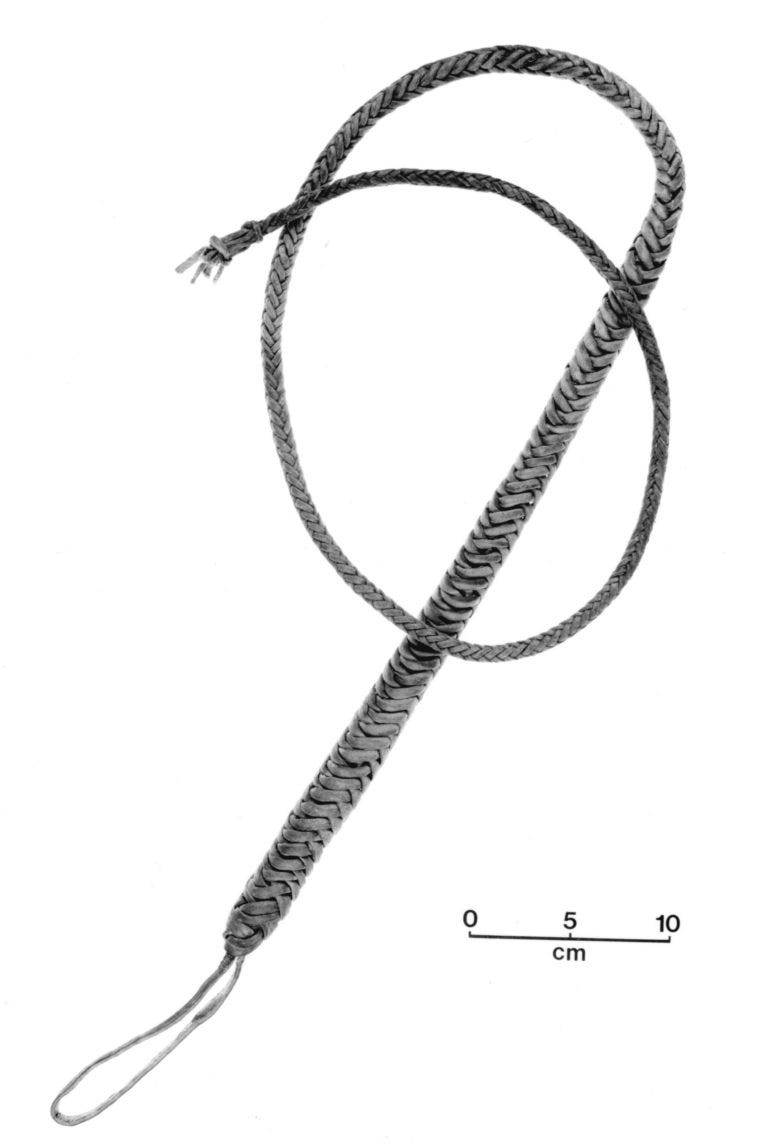

This is part one. In the next article, I’ll explore the physical violence the lash, the torture, the casual sadism that made the plantation system run. But for now, I hold space for the women and girls who were not allowed to say no, and I say this for them:

I see you. I believe you. I carry your memory with honour.

Suggested Reading / Sources:

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery

Barbara Bush, Slave Women in Caribbean Society, 1650–1838

Deborah Gray White, Ar'n't I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South

Edward Long, The History of Jamaica (1774) – [racist but illustrative of colonial mindsets]

Stephanie E. Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora

There is a book that all white women and girls (I'd probably say aged sixteen upwards), should read along with the list here. It's called "They Were Her Property", and it's written by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers:

https://www.stephaniejonesrogers.com/book

Dear Esheru,

I did not realize how much I would truly appreciate this article, thank you! You touched on points that speak volumes without softening the language and laid out facts. I look forward to the upcoming articles in this series. Until then, just like you, ... "I hold space for the women and girls who were not allowed to say no, and I say this for them: I see you. I believe you. I carry your memory with honour." 🕯️